Home

Zimbabwean Politics

- Details

- Written by: Justin Prince Chihurani and CDF

- Category: 46 Years as at 18th April 2026

- Hits: 124

Zimbabwean Politics - Vision 2030 & Human Rights Violations

Zimbabwean Politics - Vision 2030 & Human Rights Violations

Zimbabwe’s political situation remains complex and highly debated, especially as the government continues to promote its Vision 2030 plan. Under President Emmerson Mnangagwa and the ruling party ZANU-PF, Vision 2030 aims to transform Zimbabwe into an upper-middle-income country by the year 2030. The plan focuses on economic growth, infrastructure development, and attracting foreign investment. While these goals sound promising, many citizens question whether meaningful development can happen without political reforms and respect for human rights.

In principle, Zimbabwe’s development goals are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which promote poverty reduction, equality, and improved living standards. However, achieving these goals requires strong institutions, transparency, and accountability. Many Zimbabweans believe that corruption, lack of accountability, and political repression continue to hold the country back.

Human rights remain a major concern. Reports from organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch frequently highlight issues including the arrest of opposition members, restrictions on public protests, and intimidation of journalists and activists. In several instances, security forces have been accused of using excessive force against citizens who are expressing dissatisfaction with the government. Such actions create fear and discourage people from freely participating in political life.

Elections have also been controversial. There have been ongoing concerns about fairness, transparency, and the independence of key institutions. When citizens lack confidence in the electoral process, it weakens democracy and undermines trust in national development plans like Vision 2030.

In my view, economic development and human rights cannot be separated. For Zimbabwe to truly achieve its 2030 vision, there must be genuine respect for democratic principles, freedom of expression, and the rule of law. Without addressing these concerns, Vision 2030 risks becoming more of a political slogan than a reality that improves the lives of ordinary Zimbabweans.

See after "READ MORE" - Tweet from CDF who were trying to conduct a meeting regarding the Constitution https://x.com/cdf

Digital Services Tax

- Details

- Written by: Chipo Musarurwa Siziba @ChipoMusarurwaS

- Category: ZEXIT

- Hits: 262

Digital Services Tax

Digital Services Tax

As taken from X/Twitter x.com/ChipoMusarurwaS Image by TAKBATANA [Click on Image for a larger version - opens in a new window]

The recent introduction of the Digital Services Tax is not just another levy it is an act of economic aggression against a population already stretched to its limits.

But while this new tax has rightly sparked outrage, it is merely the tip of the iceberg. Everything is going up this year. Why? Because the government has quietly increased the Value Added Tax (VAT) to 15.5%.

This isn’t just a number on a spreadsheet it’s a direct hit to every household’s budget. It means:

- School fees will rise, making education even more inaccessible for struggling families.

- Groceries will cost more, forcing parents to choose between meals and rent.

- Fuel and transport will spike, driving up the price of everything else.

- Electricity, mobile data, gym subscriptions, clothing, medicine nothing is spared.

This is not fiscal policy. It is extortion masquerading as governance. A Government That Takes and Takes

What do we get in return for these taxes? Crumbling roads. Empty hospitals. Underpaid teachers. Power cuts. Water shortages. A currency in freefall.

A government that taxes so much yet delivers so little is not just inefficient it is indifferent. It is a government that has lost its moral compass, prioritizing revenue collection over public service.

The Shared Struggles of Venezuela and Zimbabwe

- Details

- Written by: John C Burke

- Category: ZEXIT

- Hits: 306

Parallels in Peril:

Parallels in Peril:

The Shared Struggles of Venezuela and Zimbabwe

In the wake of Nicolás Maduro's removal from power in Venezuela, voices from the Zimbabwean diaspora have drawn stark comparisons between the two nations, urging similar international action against Zimbabwe's President Emmerson Mnangagwa. Both countries, once promising economies bolstered by abundant natural resources, have descended into cycles of political instability, economic collapse, and human suffering.

This article explores the eerie similarities in their trajectories: rigged elections, eroded democratic institutions, systemic corruption, human rights atrocities, untapped mineral wealth, and the potential role of U.S. assistance in restoring stability to Zimbabwe.

Rigged and Stolen Elections:

A Pattern of FraudElection manipulation has been a hallmark of governance in both Venezuela and Zimbabwe, undermining public trust and perpetuating authoritarian rule. In Venezuela, the 2024 presidential election was marred by widespread fraud, with the National Electoral Council (CNE) declaring Maduro the winner without releasing disaggregated results or allowing independent verification. Opposition tallies showed Edmundo González Urrutia winning by a landslide, yet Maduro's regime suppressed evidence and resorted to repression. gjia.georgetown.edu Independent analyses, including those by the Associated Press and election forensics experts, confirmed the scale of the manipulation, labeling it a blatant theft of the people's will. gisreportsonline.com

Zimbabwe mirrors this with its 2023 elections, where President Mnangagwa secured a second term amid allegations of massive irregularities. The opposition Citizens' Coalition for Change (CCC) rejected the results, citing voter suppression, delayed polling, and intimidation by groups linked to the ruling ZANU-PF party. Regional observers from the Southern African Development Community noted these flaws, questioning the election's credibility.

Donor Dependency

- Details

- Written by: Independent80

- Category: ZEXIT

- Hits: 278

How long should Zimbabwe be donor dependent?

How long should Zimbabwe be donor dependent?

The issue of the length of time the Zimbabweans will have to continue relying on the international donors is acute. Even with the international donor efforts to alleviate livelihoods by introducing different interventions, the government of Zimbabwe tends to misuse funds which are provided by various economic sectors.

Another major issue is when the projects funded by the donors are finished and have to be certified by one of the appropriate ministries. Government authorities in Zimbabwe are often heard to take 'credit' in these projects thus deceiving their populations by insinuating that the donors are simply reclaiming what is theirs or simply not acknowledging the contribution of the donors.

Furthermore, the government fails to make any assurance of the sustainability (see below) of these projects resulting in the degradation of structures and restoration to the normal state of suffering. The question that this cycle evokes is why various donors tend to repeat the same projects soon after. The corrupt nature of the Zimbabwean government incapacitates the communities and line ministries. It also, limits the sustenance of projects and sustenance of dependency as a result of donors. This has implications to the donors.

The projects that are launched today cannot be projected to be sustained on the local resources in the long run. The risk is infrastruct in Zimbabwe is dependent, effectively, on charity - something a legitamate goverment should never do. It is the function of a competent government to provide and maintain infrastucture and projects. Something sadly lacking in Zimbabwe as a whole - just look at the failed sewage and water supply problems and their knock on effect on public health - another area in desperate need of government support!

The present state of donor assistance cannot be perpetuated without the occurrence of a new dimension of priorities in the world. The donors also have not knowingly gotten into a continued agreement to supply resources to the government. The use of funding on particular projects is not usually of much benefit since it places too much strain on limited administrative expertise and the locals are not sustained. There are also security concerns, drought, and administrative limitation beyond the large cities, which contribute to the ineffectiveness of aid even more.

Political Persecution

- Details

- Written by: Desire Munyaradzi KUNAKA with Claude AI as Research Assistant

- Category: ZEXIT

- Hits: 382

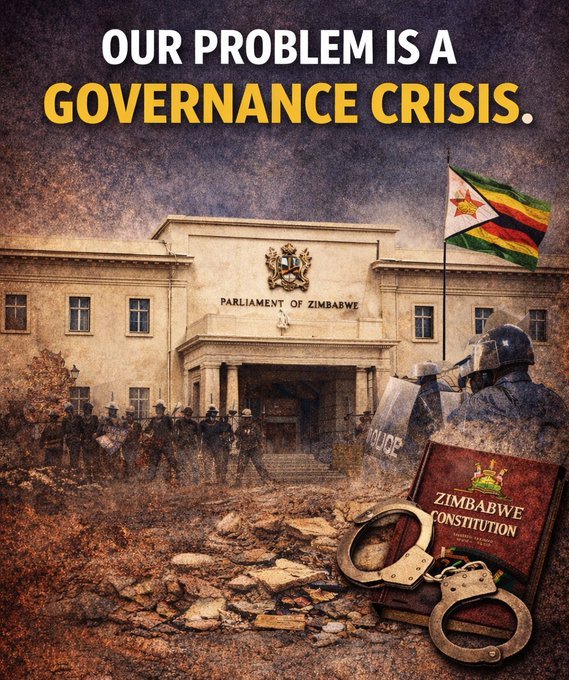

Political persecution in Zimbabwe remains a serious and ongoing issue under President Emmerson Mnangagwa's government. Here's an overview of the current situation:

Political persecution in Zimbabwe remains a serious and ongoing issue under President Emmerson Mnangagwa's government. Here's an overview of the current situation:

Recent Pattern of Repression

The authorities have continued to weaponize the criminal justice system against perceived critics and the political opposition, with impunity for ruling party ZANU-PF violence, intimidation, harassment, and repression against opposition members and civil society activists restricting civic and political space.

Scale of Human Rights Violations

According to the Zimbabwe Peace Project, 7,292 people were affected by human rights violations in February 2025, a dramatic increase from 3,161 in January 2025 and 1,460 in December 2024. These violations included threats of violence, politically motivated assaults, unfair distribution of food aid, and restrictions on freedom of assembly, association and expression.

Mass Arrests and Detention

Ahead of the August 2024 Southern African Development Community summit in Harare, authorities intensified their crackdown, arresting more than 160 people, including a religious leader, elected parliament and council officials, political activists, union leaders, students, and journalists. While many were eventually acquitted or given suspended sentences, cases of abuse in custody were reported.

Page 1 of 16